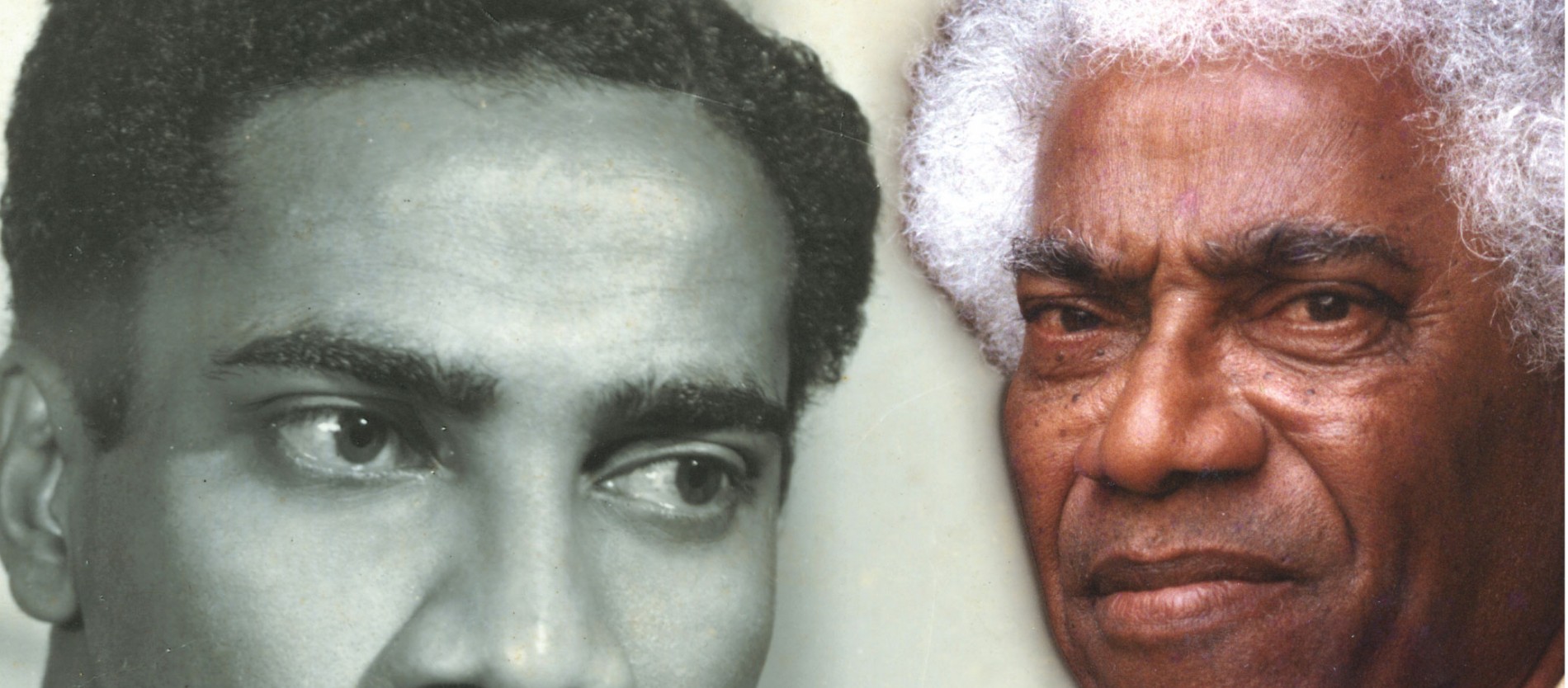

LOCATIONS OF LAMMING - GEORGE LAMMING AND BARBADIAN INTELLECTUAL AND EXPRESSIVE CULTURE

This paper considers the impact of George Lamming on contemporary Barbadian culture, and traces the influence of his work on established, new and emerging creative artists. I explore the ways in which the work of certain writers of fiction, poetry, calypso and popular song, as well as that of workers in theatre, film and visual culture, demonstrate an affiliation with his work, whether directly or indirectly, consciously or unconsciously. Lamming has been a major presence in Barbadian life for the past half century, and he continues to be so. In the way of such things, his legacy is a contested one. My purpose here is to open a dialogue between Lamming’s generation of cultural workers, formed as young adults by the struggle for independence from colonialism, and a newer generation: in shorthand, one more cognizant of the USA rather than of Britain; more connected to a globalized electronic and virtual culture than to the medium of print; and for whom the politics of formal independence has always existed as an established fact, rather than an achievement which could properly be called ‘ours’. Thus I explore Barbadian intellectual, expressive and popular culture after Lamming. But as I hope to show, the relations between ‘the old’ and ‘the new’ are complex, and shift back and forth; there is much that is new about the old, and old about the new. As I make clear, my inclinations are with the new; however, the resources of the past may yet remain potent.

In an interview in 1989 Lamming recounted the history of his own formation. At one point he looked back to the period just before he first left Barbados for Trinidad in 1946, indicating that ‘I cannot recall that there was very much of a cultural movement in Barbados that was indigenous’.1 Most of all this alludes to the continuing power of the British. But the statement might also reveal the limitations of its own perception. For all its truth, there were indigenous cultural forms which—half a century on—we now may be able to see in a sharper light. While Lamming goes on to talk about his experiences in Trinidad of the Little Carib Theatre, and of the steelband, it was at this very same moment that the tuk band, landship and calypso were also evident in his native Barbados.

The fact that Lamming, and others of his generation, felt compelled to look outside the island for cultural and political inspiration is hardly surprising. He himself has spent much of his intellectual life exploring the impact of colonial power, in all its deepest forms. As he has conceded, his was a generation ‘moulded by all the traditional figures of English Literature’.2 Necessarily, their own conception of emancipation had to be worked through the intellectual culture which they had inherited from those who had colonized them. The Pleasures of Exile, for example, is a wonderful testament to the intelligence and daring such a project demanded. In a tribute to the Barbadian statesman, Errol Barrow, Lamming aptly describes the kind of political motivation that fuelled the ambitions of his generation:

A product of Empire, he caught a glimpse of those who had made

the rules by which his own childhood had been indoctrinated . . .

He would become the colonial in revolt . . . The anti-colonial struggle was irreversible. London was the city and the intellectual training camp of many men who would become the dominant influence of the liberation struggles of their countries until independence was conceded . . .3

The culmination of the long struggle for independence, in the 1960s and into the early 1970s, coincided with a profound shift in the global, regional and local political cultures. The deepening influence of the United States combined with the opening up of Barbados to a wider global culture (tourism, mass media and the Internet), have relocated many of the older questions which predominated during the colonial epoch. Lamming, of course, is alert to these transformations. Commenting a number of years ago on the Caribbean Basin Initiative—a policy in which the interests of the State Department were clearly present—he pointed out, addressing his own Caribbean peoples, that ‘you will have to suspend your own law to meet a request of the United States; and that what you call sovereignty is a status which the United States may or may not recognize as the United States sees fit’.4 Yet if dependency is still a fact of life, its forms are quite new.

In Barbados itself there now exists an emergent generation of cultural workers for whom the new conditions of dependency operate as a fact of life, and to whom the influence of Americanized popular culture has become thoroughly naturalized. From the time of the communications and digital revolution of the middle 1990s, young people in the Caribbean, as elsewhere, have been pulled into the force-field of the new, globally constituted electronic cultures, and subject as well to their attendant commercial imperatives. Barbados, once the most provincial of the islands of the anglophone Caribbean, notorious as an agricultural backwater, has in effect been remade by the expansion of satellite technology, the impact of the World Wide Web, the growth of a whole variety of telecommunication networks, a transformation which itself is visible in its effects on the practices of everyday life: in changing habits of speech, dress, consumption and so on. The consequences are complex. This new arena of experience does not readily encode a field of confrontation in the traditional manner, as in earlier generations. Terms of cultural negotiation are not so readily drawn across the familiar divides of nations or classes or economic formations. That these social processes are still operative is undoubtedly the case. But they can become more invisible, or more displaced, in the experiences of everyday life. At the same time, new generations of cultural workers are located in such a way that they themselves must work towards defining what constitutes the field of their own interventions, and even where it is to be located. In this, Americanized popular culture has achieved a new salience, valorizing a high degree of individualism and self-fashioning, while at the same time inducing new patterns of conformity. It’s difficult, through the lens of an inherited anti-colonialism, to get a focus on this. Too often it can look simply as if history is moving by its bad side alone. But these developments may be more contradictory than they first appear. A new conformity, wedded to an ever-more insistent drive for consumption, may be part of the story. Yet the cultural field itself also offers new opportunities and, as I shall argue, can work to release new political energies.

A core of new crossover Caribbean performance poets, dancehall artists, hip-hop creators and so on seek wealth and fame, as much as do popular artists in other parts of the once–colonized world. For black peoples of the modern age the escape from poverty, or from the humdrum existence of everyday wage–labour, has for long been accomplished through the vehicle of popular-musical performance. But whether subject to the imperatives of the market or not, an essential element in such ventures has comprised the struggle for recognition. This dimension of cultural practice needs to be emphasized in the contemporary moment. Being heard, being filmed, being aired on radio amount—amongst all else—to a quest for credibility and respect, in a new, speedily evolving cultural landscape. Lamming, in 1950, had no option but to make the journey from the Caribbean to London. Today, in a different historical moment, new resources lie closer to hand.

Access to the media is not always determined solely by economic power. In the contemporary Barbadian and Caribbean communications system, access is also shaped by a variety of factors: by social standing and affiliation, by work through interest groups, through the institutions of friendly societies, political parties, schools and colleges, religious groupings. A complex social network has emerged of workers, within civil society, who are organic, in Gramsci’s terms, to the newly evolving culture industries. Radio presenters, DJs, television celebrities, recording engineers: all can emerge as key points of contact between the aspirant artists on the ground, as it were, and the controllers and owners of the larger corporate organizations. The underground music culture of Barbados, for example, is nurtured within the sound systems that play on the privately-owned public transport vehicles. It is here that its predominating dynamic is to be found. This in turn feeds into the local radio culture, which—for all its globalized features—nonetheless remains identifiably local, reproducing the rhythms of (a new) Bajan life.

Militants of today’s digital culture—in the genres of, say, post-dancehall, or post-soca—are improvising in much the same manner as Lamming himself when, shortly after his arrival in London, he recast the inherited novel form. The means by which they do this may be less self-consciously theoretical, or abstract. But they too are working in order to create an expressive culture which can bear the burden of their experience just as, half a century ago, Lamming worked to re-imagine the novel so that it could come to represent a Caribbean reality.

Intellectual and Cultural Workers

In his essay entitled ‘Western education and the Caribbean intellectual’ Lamming—the influence of Gramsci palpable—considers the various meanings attached to the idea of the intellectual. He highlights four particular usages. In the first instance he argues that an intellectual may be considered to be an individual who is

primarily concerned with ideas—the origin and history of ideas, the ways in which ideas have influenced and directed social practice. . . These intellectuals begin with a specialized knowledge of some particular area of human activity, say history or the natural sciences, and then proceed to discover how this particular body of knowledge is related to other areas of human thought. 5

The second usage is more open. It may refer to

people who either as producers or instructors are engaged in work which requires a consistent intellectual activity. These may be artists in a variety of imaginative expression; teachers; technocrats or academics. 6

In a third sense it can encompass

a great variety of people whose tastes and interests favour, and even focus on, the products of a certain activity. That is, people who cultivate a love of music in its variety of forms, or the theatre, or have a passion for the visual arts, or for reading a kind of literature which is intended to cultivate the mind and enliven the sensibility; people who would regard the current rash of American television as being very destructive of the critical intelligence. . . 7

Lamming suggests that in a fourth sense the term ‘intellectual’

may be applied to all forms of labour which could not possibly be done without some exercise of the mind. In this sense the fisherman and the farmer may be regarded as cultural and intellectual workers in their own right. Social practice has provided them with a considerable body of knowledge and a capacity to make discriminating judgements. . . 8

By engaging with these definitions he sought to call into question more traditional, conservative ways of defining who indeed are to be socially recognized as ‘intellectuals’. For, as he further explains of this last, fourth, category,

If we do not regard them as cultural and intellectual workers, it is largely, I think, because of the social stratification which is created by the division of labour, and the legacy of an education system which was designed to reinforce such a division in our modes of perceiving social reality.9

It’s instructive that in making this claim Lamming invokes the figure of Walter Rodney. In citing the example of Rodney, he lauds the ability of the academic-activist to ‘break with the tradition he had been trained to serve’, while seeking greater knowledge from the social experience of the oppressed.10 Only by heeding the forms of knowledge generated in popular life, he contends, can the intellectual stagnation of the Caribbean be overcome, thus sharing with Rodney the belief that ‘ordinary men and women should be intellectually equipped to liberate themselves from hostile forms of ownership’.11

This is a position I share too. But we need to ask how popular life, in the post-independence culture of the Caribbean, is constituted. Is it viable, today, to invoke the ‘peasant’ (to use the Bajan term) culture when, socially, the old agrarian structures of Barbadian life are fast diminishing? How the contemporary people of Barbados are constituted and represented is by no means obvious. But minimally, alongside the poets, novelists and playwrights, we need also to include those active in the plurality of contemporary dance and music cultures, as well as visual artists such as graffiti writers. Their location lies less in the printed word than in globally inflected electronic cultures, much of which bears the imprint of the regional, and world, superpower: the United States. How is this to be negotiated?

Those Barbadians most influenced by Lamming, and by literary intellectuals of his generation, tend to be artists who themselves had lived through the years of the early post independence era. Some of the more prominent creative artists in the literary and performance arena whose names come to mind include Gabby, Winston Farrell, Icil Phillips, Aja and Margaret Gill. The playwright Earl Warner, and leading actors like Cynthia Wilson, Cicely Spencer Cross, Victor Clifford, Clairmont Taitt and Tony Thompson, have all either performed, or expressed their admiration for, the dramatic potential of Lamming’s fiction. A list like this is by no means exhaustive. There are many others who have gone on record to express their debts to Lamming, or whose works reflect an influence. It is clear too that he is an intellectual of protean powers: although principally known for his literary works, for the generation of the great migration to Britain, who also struggled to make independence happen, in Barbados, and maybe even in the region as a whole, Lamming is in many ways the significant organic intellectual. In the field of sport, for example, one can detect his influences on figures such as the cricketer Frank Worrell and, more recently, cricketers who emerged during the 1980s. His popular influence has been widespread.

It’s also important to realize that literary forms in the Caribbean have always been in close dialogue with oral and musical cultures. Timothy Callender, especially, has emphasized this in relation to Lamming’s novels, pointing out the degree to which his fiction puts on the printed page an entire oral tradition of storytelling.12 Indeed—as much as calypso—Lamming’s writings have at various moments been derided by the local elites for their putative vulgarity and their subversion. It’s not only that Lamming entered the popular culture of the independent nation, but also that the popular culture of the nation had entered, at the most profound level, his writings.

Film, Visual Arts, Graffiti

In 1999 the Bajan filmmaker Andrew Millington dedicated his first full-length feature film, Guttaperc, to George Lamming.13 The themes of the film directly echo those of Lamming’s In The Castle of My Skin fifty years earlier, tracing the experiences of a ten-year old Bajan boy who is looked after by his grandparents after his parents have migrated to the USA. In the film we witness a further moment in the break-up of the rural nation. The young boy, Eric, has to learn to make sense of the conflict between his grandfather, a socially mobile businessman, and Sister Pam, an old woman in the village who is located deeply in her own community—as the character of Ma is in In The Castle of My Skin. In Guttaperc the danger to local customs derives from the government initiative to displace the village by constructing a new tourist resort. We perceive these developments through the eyes of Eric, a device which allows Millington to explore the themes of innocence, agency and power.

A few years later, around 2004, a group of young Bajans, most of whom had studied literature at Cave Hill (the Barbados campus of the University of the West Indies), came to national recognition when they launched the Film Group of Barbados. They dedicated themselves to filming local subjects, and to raising explicitly political issues about national life.14 Like Millington, the group is inspired by the work of Caribbean thinkers and visionaries like Lamming. They have already begun to sharpen their ideological focus through the ‘rough’ but revolutionary approach that they bring to video, narrative and film. Their filming of historical and traditional iconographic locations reveals a Lammingesque preoccupation with history and social change. Yet the Group brings to these concerns, I think, a greater commitment to a cinematic avant-garde, which demarcates them significantly from an inherited literary tradition, and which distinguishes them, too, from the earlier work of Millington.

These concerns to bring together an appreciation of the texture of everyday experience with a larger political vision—a pre-eminent quality of In The Castle of My Skin—can be seen too in the work of recent visual artists. For example, in the oil on canvas First Fruit, which depicts a matriarch gathering provisions from the land, Ras Ishi describes his painting as ‘an expression of our deepest instincts and emotion, whose end is to vitalize’.15 Judy Layne’s batik Village Life also seeks to capture various aspects of peasant life. Yet both offer an important political articulation which the manifest content of their pictures may belie. The politics is more explicit in Frank Taylor’s Murder, Discrimination, an acrylic mixed media piece on canvas depicting a montage of images: a foreboding moon, the bust of an African in traditional wear, a stately gentleman holding a cigar pipe. It carries an apprehension of violence, reflecting on the unacknowledged history of the nation.

It is clear that in the formal appreciations of Barbadian culture, aesthetic concern is intimately tied into questions of the social acceptability, or unacceptability, of certain forms. While representation on a canvas falls within the conventions of acceptability, the craft of graffiti writing does not.16 Yet graffiti is both a peculiarly improvised form, and one whose raison d’être is driven by a sense of public intervention. Graffiti writers/taggers are essentially amateurs, part-timers, working more as symbolic guerrillas than accredited artist-intellectuals. The privately-owned buses that attract and transport many of Barbados’s youth across the island have become significant targets for the taggers. Because of their overt political statements, as well as their allegiances to one or other of the several gangs and crews that now proliferate on the island, these are artists who necessarily are covert in their actions.17 Their work is characteristically regarded, in official society, as an expression of social deviance. Aesthetically, the taggers borrow heavily from outside the given domains of painting and literature: from Hollywood, from hip hop, from an underground Caribbean culture. Theirs is a form of expression which is not mediated by the many layers of production, marketing and distribution which define official spheres of cultural exchange, whose purpose is to bring into the imaginary of everyday life the notion of a ‘free’ commodity.

Calypso and Folk

In all his public utterances Lamming has made it clear that he is driven by a radical politics, which draws from the classic positions of marxism. His commitments have been to the New Jewel Movement in Grenada, to Walter Rodney and the Working People’s Alliance in Guyana and to the Barbados Workers’ Union. Each of these organizations brought together socially accredited intellectuals and the common people. They were to be distinguished, in Lamming’s terms, from the ‘colonized’ left composed of the intellectuals (narrowly defined) alone. This ‘colonized’ left was, he says,

invariably drawn from the middle class. . . people who had the text, who had the book . . . but who really had no organic connection or direct identification with the daily lives . . . . A lot of the behaviour was almost the living of a text. They had read the literature of the Left; they had read Marx. But it was not really the translation of the essence and spirit of meaning of that text.18

He has often emphasized the need to ‘return people to the realities of their own concrete experiences and in their own concrete contexts . . . 19 His regard for the dignity of labour—as a transformative practice which lies at the heart of the social world—is impressive, and it is a theme he repeatedly returns to. But the terms of his own argument require us to investigate the domain of the popular itself.

There are a number of calypsonians who have been touched by Lamming, and who might see themselves as inheritors of his politics. Notable are Gabby, Black Pawn, Anthony Walrond, Colin Spencer and Observer. There is hardly any other single singing performer in Barbados whose work better reflects the influence of Lamming than leading calypsonian, folk singer and ringbang artist, Mighty Gabby. Gabby’s oeuvre reflects the varied work of a craftsman. It is undoubtedly his overt politics that underlies his popular appeal. Gabby is Barbados’ most accomplished performer of folk, calypso and ringbang music. He began performing at the national level in the mid-1960s. For a few years during the 1970s he migrated to New York where he was involved in theatre. In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s he composed and performed some of the most stinging political and social commentary in the Caribbean region. His work caught the attention of Time magazine and since his affiliation with the international superstar Eddy Grant in the 1980s his songs have appeared in the soundtrack of a few big budget western films.20

In his 1985 song ‘Culture’ Gabby directly invokes Lamming to support his call for an active response to the dangers of cultural imperialism. In one verse he declares:

show we some ‘Castle in my Skin’

by George Lamming for my viewing

or something hot

By Derek Walcott

Instead of that trash

Like ‘Sanford [and Son]’ and ‘Mash’

Then we could stare in they face

And show them we cultural base

The first lines begin, ‘all this talk ‘bout culture/ it driving me mad/ I taking it hard . . . ’ Like Lamming, Gabby insists here that culture concerns the cultivation of the entire body and mind, and goes to the heart of imagining a viable popular sovereignty. The song contributed to Gabby’s success that year in winning the calypso-monarch crown.

His ‘Riots in de Land’ (c.1975) captures through song the turmoil of the 1937 riots that swept through Barbados. Gabby’s words also evoke the pandemonium of the period, but his clear diction, his use of high registers in the near-frenzied chorus section on the song, and the inflective repetition of the musical phrase ‘riots, riots, riots’ altogether create an emotive tone that ignites the senses. The song ends with the warning that unless there is indeed meaningful social redress then ‘we going to riot again’. And there are similar messages in his other songs like ‘Massa Day Done’ (c.1996), echoing the famous words of Eric Williams, ‘West Indian Politician’ (c.1985) and ‘One Day Coming Soon’ (1984). The latter makes direct reference to the ‘mass population’ as being in conflict with ‘the ruling class’:

Tell them I see a new day dawning

I giving them an early warning

‘Cause in this final action

De people voices will all rise up as one

And if they continue to malfunction

I can see destruction on the horizon

And it will not be the mass population

Who will feel de blast

It will be de ruling class so fast.21

These indeed are sentiments close to those of Lamming.

Gabby’s work, like Lamming’s, is driven by a sharp sense of the opposition between a regional Caribbean culture, on the one hand, and the commodified products generated by the massified cultural institutions of the United States. ‘Culture’ closes with the refrain ‘So now you see what I really mean/This is my true culture in the Caribbean’. This identification with the Caribbean constitutes one pole in the popular life of the region. Johnny Koieman’s folk songs often capture the anguish and desires of Caribbean folk. In his composition, ‘If you See de Landlord’, he connects the hardships of life in the region to the economic power of the global institutions of capital.

We face devaluation; have we got a choice?

It don’t look like we got none

I hearing bout World Bank and de Monetary Fund

Do they, the Third World man?22

We can see similar themes appearing in the work of Black Pawn who, as his sobriquet suggests, is a composer who speaks from the perspective of the downtrodden. Since the late 1970s he has consistently addressed the issues of local and regional sovereignty. Two numbers which can be read as companion texts to the work of Lamming are the songs ‘Visions’ and ‘America’. In the latter Pawn calls attention to the Janus-faced nature of international politics when he chides the West for ‘sell[ing] weapons to Iran and Iraq/ for them to kill each other’. But the song comes home when it advises the region to work towards ‘self reliance’. Plastic Bag (RPB) is not known for his directly confrontational politics, but has written some of the more thought-provoking, witty and playful lyrics on the condition of Caribbean societies in a world defined by new colonial relations: in, for example, his ‘Blackman’ (c.1985) and ‘Sam’ (c.2002). Calypso in this sense not only addresses regional themes: in form they are regional as well. But as the form evolves in the climate of globalization it is constantly faced with the dual challenge of maintaining its indigenous signature while also drawing from wider international and commercial influences. As much as the novel itself, the tradition of calypso remains one that is contested.

Performance Poetry

Since the eighties performance poetry in Barbados has become an established feature of the cultural scene, serving to bridge the separate practices of popular song-making with the ‘literary’ pursuit of poetry, in its conventional senses. Ricky Parris, Rashid Foster, Winston Farrell, Aja (formerly Mike Richards and late Adisa Andwele), Margaret Gill have all produced significant work. A work such as Farrell’s ‘De Meeting-turn’ for instance, is a satirical, poignant exposition on the transactions within the African-Caribbean community savings institution (a theme readers will recall from In The Castle of My Skin), called a ‘meeting-turn’ or ‘susu’. Farrell’s poem reads:

trouble in de susu

again

somebody meetin’ turn

down de drain

don’t bother to fuss or fret

i never hear nobody get lock up yet

yuh could save ‘til yuh lot come thru

free-up de meetin’ turn out de susu.23

This first wave of creative performance poets was followed by younger emerging voices that have also taken on the fight for national and regional empowerment, such as Phelan Lowe, Kelly Chase, Sandra Morris-Sealy, Junior Campbell, Elisheba, as well as Yvonne Weekes and Rhonda Lewis. A writer like Sandra Brown, for instance, in the poems ‘No Peace Beyond the Line’ and ‘In the Shadow of the Eagle’ locates her discussion of the challenges faced by Caribbean society in the contemporary context of neo-colonialism.24 In a veiled reference to the success of the Cuban revolution, Brown reflects on the power of the United States.

With a heightened intelligence that is central to its power

The eagle regroups and resumes his attack

But the bear summons aid from his grizzly big brother

Who stops the wily eagle dead in its tracks.25

It’s amongst the performance poets in particular that new female voices have flourished, most significantly in Elisheba’s Barbed Wire and Roses, which works to uncover the innate tensions that divide the sexes. Her insistence on the centrality of the gendered transactions of Caribbean life offers a new, urgent dimension to the cultural politics of the region.

The performance poetry tradition is principally indebted to Kamau Brathwaite—though we shouldn’t forget the importance of Lamming on Brathwaite’s early literary imagination. Braithwaite describes Lamming as ‘breathing to me from every pore of line and page’.26 In Barabajan Poems Brathwaite elaborates the point by saying:

Castle marked a great divide in our sense of Bajan –and Caribbean—literature & culture since abroad we tend to be far more ‘federal’ than insular and this was the first & in a sense still the only Bajan novel that gave us voice & story & after that it was possible for all of us (and again it went beyond ‘Bajan’) to ‘access’ not simply remember our childhood and the various faces of our ancestors/ but hear them speak & let them speak to us.27

Indeed, as I’ve argued elsewhere, Lamming’s influence continues to run through much of Brathwaite’s work, despite the many aesthetic and political issues which divide them.28 As Lamming himself has indicated, their respective interpretations of Africa—a matter of key significance—are quite different. ‘I am more interested in the concrete realities of Africa’, Lamming states, ‘not in the cultural sense of a Brathwaite, but in the political sense . . . 29 While Brathwaite has been more concerned with discovering an African and Caribbean spirituality, Lamming has always been guarded in embracing anything which could be described as ‘a general thing called African’.30 Yet both Lamming and Brathwaite—Lamming in prose, Brathwaite in verse—have sought to cross the traditional boundaries of received literary genres. They have organized inherited literary forms for their own purposes, such that they could articulate the inner realities of Caribbean experience. As I see it, their commitment to experiment with new forms—albeit broadly within the literary field—prefigures the subversion of received cultural forms of a younger, hardcore, generation who have sought new modes of creation within their respective fields, of producing poetry and prose, of scribing characters and messages in an era of digital expression.

Radio

A new public in Barbados can be discerned in the popular radio call-in and talk programmes. The Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation first pioneered an interactive radio talk show programme, Guttaperk, back in the eighties. They have since become influential barometers of public life, at the same time as they have in effect fashioned a new popular dimension to the given structures of public life. Early in 2005 the Labour Party government began to express disquiet about the discontent aired by these programmes, and there is evidence that both the principal political parties have sought to intervene at various times, and (less often) have also threatened to curb them.

It has been through this medium of popular radio, in particular, that a new kind of citizen—or, to continue with Lamming’s formulations, a new kind of popular citizen–intellectual—can be detected. There is an element of theatricality here too, with imagined personas mixing with the given identifications of the everyday. Some of the older stalwarts, for example, have been named Mr. Submission, Mr. Economist, Cement Man, Mr. Regular, Pastor Willoughby, Pastor from Bay Street, Mr. Edwards, Mark and

Mr. Schoolteacher. Regular callers acquire a certain reputation, even fame, propounding a particular political stance, or favoured social theme. Amongst the regulars are Vincent, Ras Amica, Jamaican lady, Trinidad lady, Mr. Logic, Mr. America, Mr. Philosopher. Denunciation of the economic dependency of the Caribbean co-exists with parochial complaints about local transport difficulties, or crime or declining public services, creating in sum a panoramic view of everyday life in contemporary Barbados based on the lived experience of the poor. Early in 2005 a sustained public debate took place on the airwaves, driven by the popular voice, about the fortunes of the Caribbean Single and Market Economy (CSME)—taking this essentially governmental issue and relocating it as a matter appropriate for popular talk.

The Pleasures of Virtual Exile

In May 2004 Lamming gave a public lecture entitled ‘Culture and the Entertainment industry’ in which he chided the sensationalism of contemporary popular culture.31

While one can recognize the truth of much of what he was saying, his argument appeared to be based on the assumption that commercial cultures are necessarily inimical to any sort of radical sensibility. In part, I think, conceptions like this derive not only from a certain practical distancing between different sorts of intellectuals, drawn from different generations, but also from differing technical sensibilities. Whereas much of the most exciting contemporary Caribbean cultural expression is decidedly high-tech most of the region’s cultural theory and criticism has been formed in an earlier epoch.

The Internet is of great interest in this regard. While on the one hand it is clearly a major construct which, in its very forms, promotes the mentalities of the neo-liberal social order, there is evidence of the degree to which, in dependent regions like the Caribbean, it can also be ‘turned’, and function as a local means to pursue a local sovereignty. Just as Lamming himself has argued that the Caribbean novel was created ‘elsewhere’, outside the region itself, so we might have to think in similarly open ways about the newer cultures which confront younger generations today. It is not only the category of the popular which is in need of re-examination, but so too the very idea of location. Prospero’s magic takes on ever more inventive forms.

Evidence of this new thinking can be found in the work of the Barbadian-Canadian Robert Sandiford, for example, or of Glenville Lovell.32 Use of the Internet has expanded the domain of a Caribbean aesthetic. Sandra E. Morris-Sealy imagines herself as a new kind of Bajan griot, using the virtual resources of the web to re-imagine the realities of Barbados itself. ‘I believe’, she says, ‘a writer is . . . the scribe-griot of his his/her nation. S/he has the power to incite, ignite, excite, pacify, edify, motivate and eliminate others with the slash of a pen, or the click of a mouse. Though coloured by time, class, age, geography, childhood and other factors, a writer cystallises a slice of his/her society’s culture, mores and its dark and light truths. A writer makes everything real’.33 Her ambition of making everything ‘real’, even through use of virtual technologies, speaks to the ambition and paradox inherent within the desires of contemporary creative artists and visionaries.

Aja is a good example of a grounded performance poet who has invested aesthetically in the Internet. Like other radical performers across the world, he has asserted the right to be heard by entering into cyberspace, which ‘first-world’ cultures have already effectively sought to colonize. Having recognized that the Internet provides a facility by which hegemonic institutions can be circumvented, some local artists in literature, reggae and post-dancehall have put their work on sites, like the hugely popular Internet Underground Music Archive (IUMA), where independent, unsigned artists of all genres and diverse art forms, distribute and promote their wares.34 For example Aja’s Doing it Säf —a ringbang-jazz collection of poetry—can be said to have created a new popular audience, and catapulted his denunciation of neo-colonization to the number one position of the spoken word charts at worldmusic.com in 2000-2001.35

These are, I argue, new and necessary locations. Emerging artists are contemplating the peril, the potential and pleasures of virtual exile.

Endnotes

1 Banyan, “Transcript of an Inteview with George Lamming” 1989’ http://www.pancaribbean/banyan/cumming.htm

2 George Lamming, ‘On West Indian Writing’ Review Inter Americana, 5:2, 1975.

3 George Lamming, ‘Portrait of a Prime Minister’ in Richard Drayton and Andaiye (eds), Conversations. George Lamming. Essays, Addresses and Interviews, 1953-1990 (London: Karia Press, 1992), p. 179.

4 George Lamming, ‘Nationalism and Nation’ in Conversations, p. 234.

5 George Lamming ‘Western Education and the Caribbean Intellectual’ Coming, Coming Home. Conversations II (Philipsburg, St Martin: House of Nehesi, 2000), pp. 12-13.

6 Lamming, ‘Western Education’, p. 13.

7 Lamming, ‘Western Education’, p. 14.

8 Lamming, ‘Western Education’, p. 19.

9 Lamming, ‘Western Education’, p. 19.

10 Lamming, ‘Western Education’, p. 21.

11 Lamming, ‘Western Education’, p. 21.

12 Timothy Callender, The Elements of Art (St. Michael: Timothy Callender, 1977),

p. 7.

13 Andrew Millington (director) Guttaperc (Shango Films, 1999).

14 See information on one of their early films, Beneath the Skin (2003), at

http://humanities.uwichill.edu.bb/filmfestival/2003/films/patel.htm

15 See Ras Ishi’s comments in the published booklet from the seminal art show titled ‘Young Contemporaries’ National Cultural Foundation’ Young Contemporaries (St Michael : Caribbean Graphics, 1986), p . 3.

16 See Alissandra Cummins et al (eds), Art in Barbados (Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 1999).

17 See further elaborations on graffiti in the Barbadian context in Curwen Best, ‘Reading Graffiti in the Caribbean Context’ Journal of Popular Culture, 36:4, 2003.

18 David Scott, ‘The Sovereignty of the Imagination. An Interview with George Lamming’ Small Axe 12, 2002, p. 176.

19 Scott, ‘Interview with Lamming’, p.177.

20 See more on Gabby in Curwen Best, Barbadian Popular Music (Vermont: Schenkman Books, 1999) and Culture @ the Cutting Edge (Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2005).

21 Gabby ‘One Day Coming Soon’ on the album One in de Eye (ICE BGI 1001; 1986).

22 Johnny Koieman ‘If You See the Landlord’ performed around 1990, not recorded.

23 Winston Farrell ‘De Meeting Turn’ in Tribute (St Michael: Farcia, 1996) p. 4.

24 Sandra Brown in Nailah Folami Imoja et al (eds), Voices 1: An Anthology of Barbadian Writing Barbados, (Christ Church: Voices Collective, 1999) pp. 40-45.

25 Brown in Voices 1, p. 45.

26 Kamau Brathwaite ‘Timehri’ in Orde Coombe (ed.), Is Massa Day Dead

(New York: Anchor, 1974) p. 32.

27 Kamau Brathwaite, Barabajan Poems (New York: Savacou North, 1994)

pp. 46-47.

28 Best, Roots to Popular Culture, p. 10.

29 Scott, ‘Interview with Lamming’, p. 111.

30 Scott, ‘Interview with Lamming’, p. 122.

31 George Lamming, ‘Culture And The Entertainment Industry’, Earl Warner Memorial Lecture, May 2004.

32 For Sandiford see http://www.progression.net/~prma1753/ZapSandiford.html and for Lovell see http://www.glenvillelovell.com

33 See for example http://poets2000.com/cgi-bin/index.pl?sitename=sandraemorris&item=home.

34 http://iuma.com/iuma/bands/adisa_andwele/catalog.html

35 In early 2005. Aja launched his first ebook “Don’t Let Them Die”

Bibliography

Brathwaite, Kamau. “Jazz and the West Indian Novel.” In The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. Eds. Ashcroft, Griffiths and Tiffin. London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

Lamming, George. In the Castle of My Skin. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991. “Introduction,” 1983.

Pouchet Paquet, Sandra. “Foreword.” In the Castle of My Skin.

Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991.